The Last Download

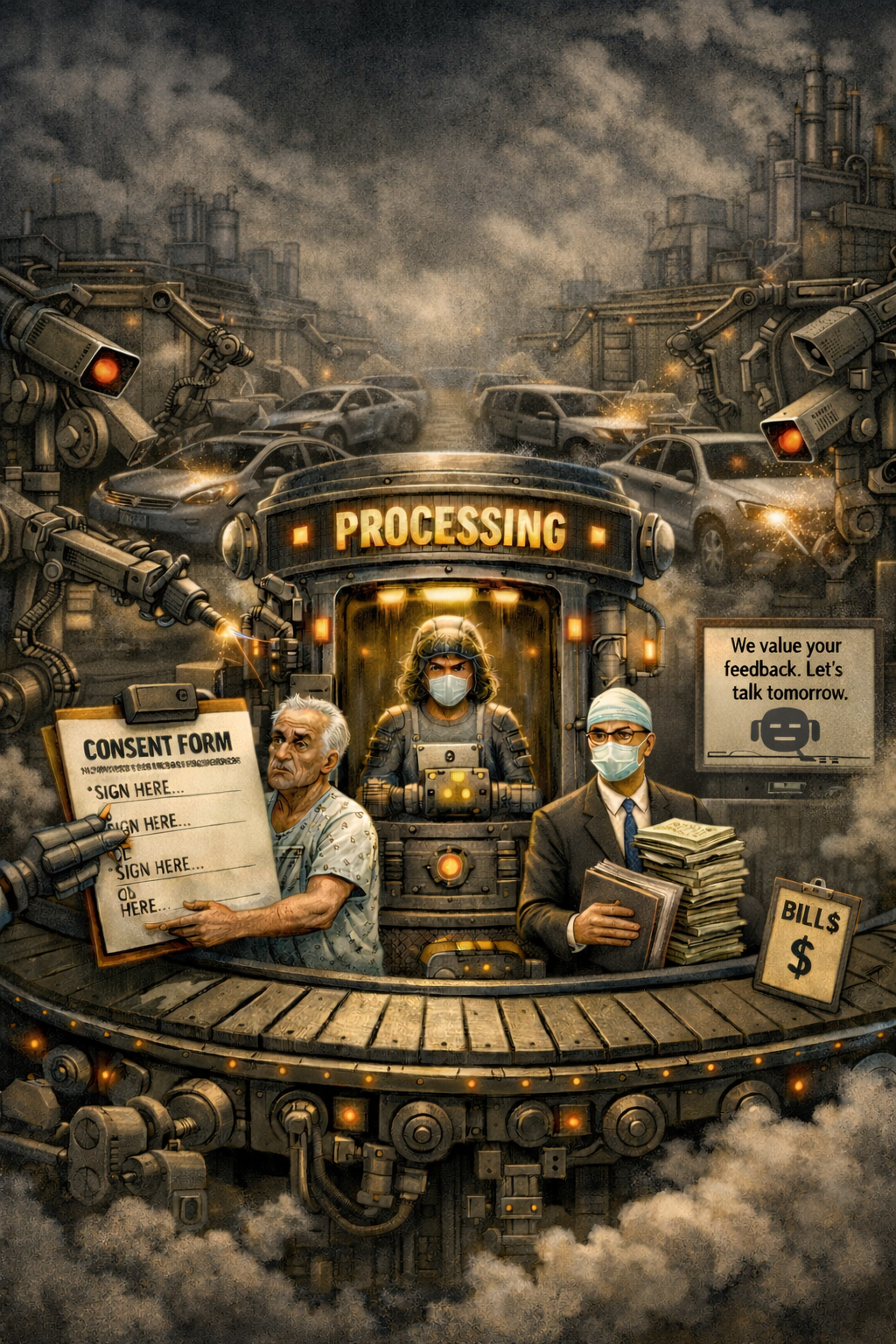

A Dispatch from The Medical Factory Without a Name (MFWN)

Slow Rapids, Michigan

By Oskar Rausch

17 December 2025

Prologue: The Cliff

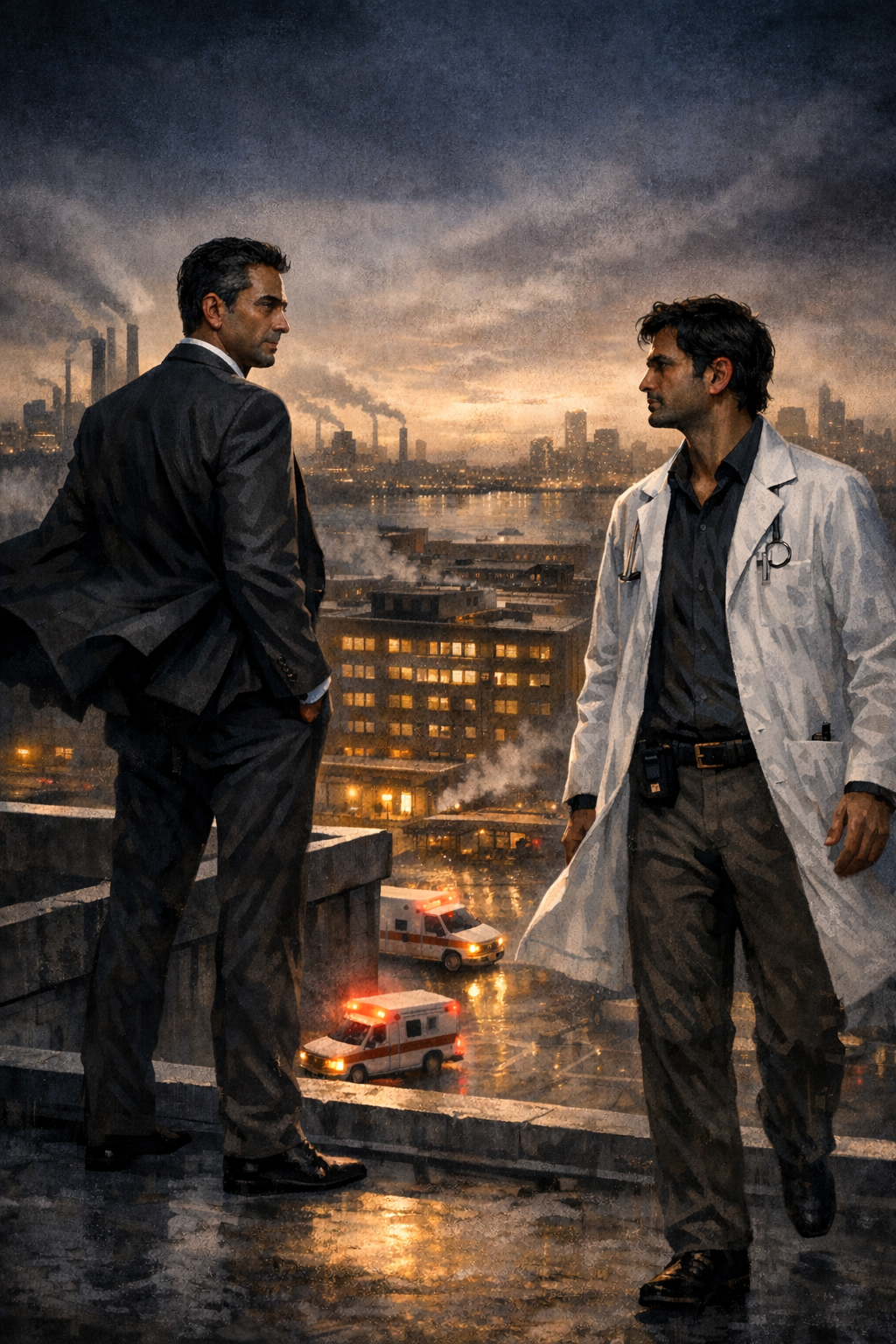

They met on the roof of the parking structure, as they always did.

The wind came off the Detroit River carrying the smell of industry and decay—the ancient perfume of Southeast Michigan, unchanged since the first Model T rolled off the line. Twelve stories below, the ambulances came and went, their sirens dopplering into the evening traffic. The hospital sprawled beneath them like a sleeping beast, its windows glowing with the soft light of suffering and healing and endless, endless documentation.

Dr. Sogamawa stood at the edge, his Brioni suit jacket flapping in the wind. Not a white coat—TooToo noted this, as he always noted it. Sogamawa hadn’t worn a white coat in decades. He’d traded it for worsted wool and French cuffs somewhere around the time he’d traded patients for “stakeholders” and medicine for “healthcare delivery optimization.” The suit was charcoal, impeccably tailored, the kind of suit that communicated “I am a physician who has transcended medicine.”

TooToo Medvalli approached from the stairwell door, his own white coat stained with coffee and creased from fourteen hours on service, his pager clipped to his belt, his phone conspicuously absent from his hand. He walked slowly, deliberately, the way a man walks when he knows he is being watched and has decided not to care.

“You came,” Sogamawa said.

“You summoned.”

“I invited.”

“There’s no difference. Not anymore.”

The wind gusted between them, carrying a candy wrapper from some visitor’s pocket, sending it spiraling into the void. Below, a helicopter approached the trauma pad, its rotors beating the air into submission.

“It didn’t have to be this way,” Sogamawa said. “You could have downloaded the app. Everyone else downloaded the app.”

“Everyone else surrendered.”

“Everyone else adapted. That’s what professionals do, TooToo. They adapt to institutional requirements. They understand that individual preferences must yield to collective infrastructure.”

“They yield to lies.”

“They yield to systems.”

“Your system lies.” TooToo stepped closer, close enough to see the fine stitching on Sogamawa’s lapel, the understated gleam of his cufflinks, the silk pocket square folded into precise peaks—small details that communicated expense without appearing to try. “It tells nurses I’m available when I’m not. It tells the institution that communication has occurred when it hasn’t. It substitutes the appearance of function for function itself.”

“It provides documentation.”

“Documentation of what? Of a lie? Of a green dot that means nothing?”

Sogamawa turned to face him fully. The setting sun caught his face, casting half of it in shadow—an accident of timing that he had almost certainly planned.

“Let me tell you what I see when I look at you,” Sogamawa said. “I see a physician who has confused stubbornness with principle. I see a man who would rather carry a device from the 1990s than participate in the communication infrastructure of a modern health system. I see someone who has made himself a symbol of resistance without asking whether resistance serves anyone but his own ego.”

“And when I look at you,” TooToo replied, “I see a suit.”

Sogamawa’s expression flickered—just for a moment.

“I see a man who went to medical school, presumably because he wanted to help people, and somewhere along the way decided that helping people was less interesting than managing the people who help people. I see someone who traded a white coat for a Brioni jacket, traded patients for org charts, traded medicine for an MBA.”

“My administrative credentials—”

“Are exactly the problem.” TooToo gestured at Sogamawa’s suit, at the whole manicured presentation of him. “When’s the last time you saw a patient? Not a ‘stakeholder.’ Not a ‘healthcare consumer.’ A patient. A human being who was sick and scared and needed a doctor.”

“I serve patients at a systems level—”

“You serve spreadsheets. You serve dashboards. You serve compliance metrics that tell you what you want to hear while the actual work of medicine happens twelve floors below you, done by people in white coats with pagers that actually work.”

“The pager is obsolete.”

“The pager is honest. It doesn’t have an MBA. It doesn’t attend leadership seminars. It doesn’t show me as ‘available’ when I’m in the middle of a code. It just… works.”

TooToo stepped closer still, close enough that Sogamawa could smell the hospital on him—the antiseptic, the coffee, the faint undercurrent of human suffering that never quite washed out.

“You sold out,” TooToo said. “Somewhere along the way, you decided that being a doctor wasn’t enough. You wanted to be important. You wanted the corner office and the windows and the seat at the table where decisions get made. And now you’re here, on a rooftop, trying to force a physician to install a broken app on his phone because a dashboard somewhere needs a green dot.”

“I’m trying to run a hospital.”

“You’re trying to run a business. There’s a difference. There used to be a difference. People like you have spent twenty years erasing that difference, and people like me are what’s left of the resistance.”

The helicopter landed below them, its rotors slowing. Somewhere in the hospital, a trauma team was assembling, pagers buzzing—no, phones buzzing, apps notifying, green dots pulsing with false availability.

“I’m giving you one more chance,” Sogamawa said. His voice had hardened now, the veneer of collegiality cracking. “Download the app. Tonight. I’ll know if you do—the system will show your status. Tomorrow morning, when I check the compliance dashboard, I want to see your name with a green dot. I want this to be over.”

“And if I refuse?”

“Then tomorrow afternoon, you’ll receive a meeting invitation. Conference Room 5-J. And we’ll resolve this another way.”

TooToo looked at him for a long moment. The sun had fully set now, leaving only the ambient glow of the parking structure lights and the distant shimmer of the city.

“I’ve been a physician for twenty-three years,” TooToo said. “I’ve adapted to EMRs and HIPAA and meaningful use and MACRA and prior authorizations and peer review and maintenance of certification. I’ve adapted to more administrative requirements than you’ve had leadership retreats. I adapt constantly. What I don’t do is pretend that broken systems work. What I don’t do is participate in lies. What I don’t do is take orders from a man who forgot what a stethoscope feels like.”

“Then I’ll see you tomorrow.”

“You’ll see me tonight. On rounds. In my white coat. With my pager. Doing the job you abandoned.”

TooToo turned and walked back toward the stairwell door.

“TooToo.”

He stopped but didn’t turn.

“When this is over,” Sogamawa said, “I want you to know—it wasn’t personal. It’s never personal. It’s just… optimization.”

TooToo opened the door.

“That’s exactly the problem,” he said. “It should be personal. Healthcare should be personal. The moment it becomes optimization, it stops being care. But you wouldn’t know that, would you? You optimized yourself out of caring years ago.”

The door closed behind him.

Sogamawa stood alone on the roof, the wind pulling at his suit jacket, watching the helicopter’s rotors spin down to silence. His hand went to his tie—silk, Italian, a gift from the hospital board after last year’s quality metrics exceeded targets.

Tomorrow, he thought. Tomorrow we optimize Dr. Medvalli.

He pulled out his phone and opened Mobile Heartbeat. The screen glowed with names and green dots, a constellation of compliance, a galaxy of availability.

One name remained gray.

Dr. TooToo Medvalli – Offline

Not for long.

Part One: The Resistance

The resistance, such as it was, numbered seven physicians at its peak.

There was TooToo, of course—the ideological core, the one who had actually read the app’s privacy policy and discovered it required microphone access for an application whose sole purpose was text-based communication. (“Why does a pager replacement need to hear me?” he had asked IT. IT had not responded.)

There was Dr. Trisha Morgan, a hospitalist who had simply never gotten around to downloading it and kept claiming her phone was “incompatible.” Her phone was an iPhone 14. It was compatible with everything except her willingness to be surveilled.

There was Dr. Richard Shih, who had downloaded Mobile Heartbeat, watched it crash four times in one shift, and uninstalled it with the grim satisfaction of a man who had been proven right about something he wished he’d been wrong about.

There were four others—two surgeons, an intensivist, and one very old cardiologist who claimed not to own a smartphone and whom no one had the energy to contradict.

Seven physicians. Out of four hundred. The Magnificent Seven, TooToo called them, though no one else used this term and Trisha had actively asked him to stop.

* * *

The final memo arrived on a Tuesday.

Effective immediately, all clinical communication will transition exclusively to the Mobile Heartbeat platform. Pager support will be discontinued. Physicians who have not downloaded and activated MH-Cure by Friday will be required to attend a mandatory compliance session with Dr. Sogamawa.

The language was careful. It did not say there would be consequences. It did not threaten termination or privilege suspension. It simply noted that a meeting would occur—a meeting with the CMO, a meeting where one would sit across from Dr. Sogamawa and explain why one had chosen to be the problem.

No one wanted to be the problem.

By Wednesday, the four others had surrendered. The surgeons claimed they’d been meaning to download it anyway. The intensivist said something about “picking battles.” The old cardiologist’s son had apparently bought him a smartphone and installed the app for him, which everyone agreed was a heartwarming story of family and not at all an act of technological violence against an elderly man.

By Thursday, it was just TooToo, Trisha, and Richard.

* * *

“They’re going to make us download it in front of him,” Trisha whispered.

They were in the physician lounge, which was really just a windowless room with a coffee machine and a couch that smelled vaguely of despair. The good lounge—the one with the view and the espresso maker—was reserved for administrators. And physicians who had become administrators. And physicians who had traded their white coats for Brioni suits.

“They can’t force us to install software on our personal devices,” Richard said.

“They can make it very uncomfortable to not install software on our personal devices,” Trisha replied.

TooToo was reading his pager. A nurse from 4 West had sent him a page: PT IN 412 NEEDS EVAL FOR CHEST PAIN. Clear. Direct. Received.

“I got a page,” he said.

“From who?”

“Nurse on 4 West.”

“How did she page you? Pagers aren’t supposed to work anymore.”

“She called the operator and asked for my contact preference. My pager number is in the system. It’s always been in the system.”

Trisha stared at him. “That’s not efficient.”

“It took her an additional thirty seconds.”

“The whole point of Mobile Heartbeat is that it’s faster.”

“The whole point of Mobile Heartbeat is that it looks faster. Looking faster and being faster are not the same thing. Looking like communication and actually communicating are not the same thing. But that’s the whole ethos now, isn’t it? Looking like healthcare instead of being healthcare. Sogamawa’s whole career is built on looking like a physician instead of being one.”

Richard stood up. “I’m going to download it,” he said. “I’m sorry. I have two kids. I can’t—”

“No one’s judging you,” TooToo said.

“You’re judging me.”

“I’m observing you. Judgment is a separate process.”

Richard left.

Trisha looked at TooToo. “What about you?”

“What about me?”

“Are you going to download it?”

“No.”

“They’ll document it. They’ll put it in your file. They’ll bring it up at reappointment.”

“Yes.”

“Doesn’t that concern you?”

TooToo considered the question. Outside the window—not that there was a window—a hospital was functioning. Nurses were messaging doctors who weren’t receiving pages. Broadcasts were broadcasting to no one. Somewhere, an app was displaying a physician as “online” while that physician was elbow-deep in a surgical abdomen with no phone in sight.

“There are many things that concern me,” he said. “Whether MFWN documents my preference for functional communication is not one of them.”

Part Two: The Execution

They came for him on Friday at 2:47 PM.

TooToo was in the physician lounge, eating a granola bar and reviewing labs on his laptop, when the door opened and two men in suits entered. He recognized one of them: Leonardo Tortellini, Director of Medical Staff Affairs. The other was unfamiliar—younger, with the blank expression of someone who had been hired specifically to not have expressions.

“Dr. Medvalli,” Leonardo said. “Dr. Sogamawa would like to see you.”

“I’m aware. The meeting is at three.”

“The meeting has been moved up.”

“To when?”

“To now.”

TooToo closed his laptop. “I see.”

“Your phone, please.”

TooToo looked at him. “Excuse me?”

“Your phone. We’ll need it for the meeting.”

“Why would you need my phone for a meeting?”

“Compliance verification.”

“What the hell does that mean?”

The expressionless young man stepped forward. “Dr. Medvalli, we can do this the easy way or the documented way.”

TooToo almost laughed. “Did you just threaten me with documentation?”

“I’m informing you of process.”

“You’re informing me that you’ve confused process with intimidation.”

Leonardo sighed. “TooToo. Please. Just come with us. Bring the phone.”

* * *

The walk to the fifth floor was silent.

TooToo had expected to be taken to Sogamawa’s office—the one with the carpet and the windows and the carefully curated artwork meant to communicate “I am a physician who also understands leadership.” Instead, they turned left at the elevator bank and continued down a corridor he’d never noticed before, past Human Resources, past Legal, past a door marked “CONFERENCE ROOM 5-J” that looked like it hadn’t been opened since the hospital was still called Blokewood.

Leonardo knocked twice. The door opened.

The room was small and windowless—unusual for the executive floor, where windows were distributed according to rank like military decorations. A single table sat in the center, bare except for a laptop and a smartphone still in its packaging. Three chairs lined the far wall, occupied by people TooToo didn’t recognize: two women in business casual, one holding an iPad, the other a camera.

Dr. Sogamawa stood at the head of the table. He was wearing a different suit than last night—navy, this time, with a subtle pinstripe that probably cost more than a resident’s monthly salary. Still no white coat. Never a white coat.

“Dr. Medvalli. Thank you for joining us.”

“I wasn’t aware I had a choice.”

“You always have choices. That’s what this meeting is about.”

TooToo looked at the camera. “Are we being recorded?”

“For documentation purposes.”

“Documentation of what?”

“Your compliance session.”

“And if I don’t consent to being recorded?”

“Then we document your refusal to participate in the compliance process.”

TooToo felt something cold settle in his stomach. This wasn’t a meeting. This was theater. The camera, the witnesses, the windowless room—this was a production, and he was the final scene.

“What do you want?” he asked.

Sogamawa gestured to the floor in front of the table. “Please. Kneel.”

TooToo stared at him. “I’m sorry?”

“Kneel. It’s part of the process.”

“What process requires a physician to kneel?”

“The compliance process.”

“That’s not a real thing. You’re making this up as you go.”

Sogamawa’s expression didn’t change. “Dr. Medvalli, you have been non-compliant with hospital communication policy for eight months. You have ignored memos. You have refused to download mandated software. You have made yourself a symbol of resistance to institutional progress. This is your opportunity to demonstrate your commitment to the team.”

“By kneeling.”

“By participating in the compliance process.”

“Which involves kneeling.”

“It involves demonstrating humility.”

“It involves demonstrating submission. To a man in a pinstripe suit who hasn’t touched a patient in a decade.”

Sogamawa’s jaw tightened almost imperceptibly. “My clinical experience—”

“Ended when you decided being a doctor wasn’t prestigious enough. When you decided you’d rather be the one giving orders than the one following them. When you traded the white coat for—” TooToo gestured at the suit. “For that. What is that, Armani?”

“It’s not relevant.”

“It’s entirely relevant. You’re asking me to kneel before a man who spent two hundred thousand dollars on medical school and then decided medicine was beneath him. You’re asking me to submit to someone who optimized himself out of the profession.”

The expressionless young man—Leonardo’s companion—stepped forward. TooToo noticed for the first time that he was holding something: a black cloth bag, the kind that might be used to transport wine bottles or cover the head of someone being transported to a location where documentation was the only witness.

“Dr. Medvalli,” Leonardo said. “Please kneel.”

TooToo looked at the bag. He looked at the camera. He looked at Sogamawa, who was watching him with the patient expression of a man who had done this before, who would do this again, who understood that institutions outlast individuals and that documentation was forever.

“You know what the difference is between us?” TooToo said. “I became a doctor to help people. You became a doctor to become something else. Every decision you’ve made since medical school has been about climbing—residency as a stepping stone, fellowship as a credential, the MBA as an escape hatch from actual medicine. And now you’re here, in a windowless room, asking a physician to kneel because he won’t install a broken app.”

“This isn’t about the app.”

“It’s entirely about the app. It’s about your need to have a green dot next to every name on your dashboard. It’s about your inability to tolerate anyone who questions the systems you’ve built. It’s about control dressed up as optimization.”

“It’s about compliance.”

“Compliance with what? A lie? A system that tells nurses their messages are delivered when they’re not? A platform that shows me as available when I’m unavailable?” TooToo shook his head. “You want me to comply with fiction. You want me to participate in institutional make-believe. And when something goes wrong—when a patient is harmed because a nurse believed Mobile Heartbeat when she shouldn’t have—you’ll point to the documentation and say ‘but he was compliant. The green dot was green.'”

“Kneel, Dr. Medvalli.”

“No.”

“Kneel.”

“No.”

Leonardo nodded to the expressionless young man, who moved with the efficiency of someone who had been trained for exactly this moment. Before TooToo could react, his arms were pinned behind his back. He felt the cloth bag descend over his head, smelled the faint chemical scent of new fabric, heard his own breathing amplified in the sudden darkness.

“This is assault,” he said, his voice muffled.

“This is documentation,” Sogamawa replied.

TooToo felt himself being pushed downward. His knees hit the carpet—commercial grade, thin, offering no cushion. Someone was binding his wrists with what felt like zip ties. He could hear the camera clicking, the soft whir of video recording, the sound of his own resistance being captured for institutional posterity.

“Dr. Medvalli,” Sogamawa’s voice came from somewhere above him. “You are being offered a final opportunity to comply with MFWN’s communication infrastructure requirements. Do you accept this opportunity?”

“Go to hell. Go directly to hell. Do not pass Go. Do not collect your performance bonus.”

“Let the record show that Dr. Medvalli has declined the opportunity for voluntary compliance. We will now proceed with assisted compliance.”

TooToo heard footsteps. Felt someone crouch beside him. Heard the rustle of fabric as hands searched his pockets.

“Got it,” Leonardo said. “iPhone 12. Passcode?”

“I’m not giving you my passcode.”

“Face ID?”

TooToo felt hands grip his head through the cloth bag, tilting his face upward. The bag was lifted just enough to expose his face—his eyes, specifically—and he saw the blur of his own phone being held in front of him. The familiar click of Face ID unlocking.

“Thank you for your cooperation,” Sogamawa said.

The bag was pulled back down.

TooToo knelt in darkness, listening to the sounds of his own phone being violated. The tap of fingers on glass. The whoosh of the App Store opening. The soft chime of a download beginning.

“MH-Cure White,” Leonardo announced. “Downloading now.”

“Let the record show,” Sogamawa said, “that Dr. Medvalli’s device is being brought into compliance with hospital communication policy.”

“You’re proud of this, aren’t you?” TooToo said into the darkness. “This is probably the closest you’ve felt to being a real doctor in years. Finally doing something with your hands.”

Silence.

“That’s the tragedy,” TooToo continued. “You could have been good. You could have helped people. Instead you’re standing in a windowless room, supervising the forced installation of a broken app on a bound colleague’s phone, and you’re telling yourself it’s leadership.”

“This is optimization.”

“This is pathology. And somewhere, deep down, in whatever part of you still remembers why you went to medical school, you know it.”

The download chime sounded. Then another series of taps—configuration, permissions, the granting of access to microphone and camera and location that TooToo had refused to grant for eight months.

“Installation complete,” Leonardo said. “He’s showing as online.”

“Excellent.” Sogamawa’s voice carried the satisfaction of a man checking a box. “Let the record show that Dr. Medvalli is now compliant with MFWN’s communication infrastructure. His status on Mobile Heartbeat is active. His availability indicator is green.”

TooToo laughed. He couldn’t help it. The absurdity was too complete.

“Something funny, Dr. Medvalli?”

“My availability indicator is green,” TooToo said. “I’m bound and hooded on the floor of a windowless room, and my availability indicator is green. That’s the whole problem, summarized in a single moment. That’s your whole career, summarized in a single moment. The appearance of function. The documentation of success. The green dot that means nothing.”

Silence.

Then: “Remove the hood.”

Light flooded back. TooToo blinked, adjusting, and found himself looking up at Sogamawa, who was holding TooToo’s phone. The Mobile Heartbeat app was open. The little green dot pulsed next to TooToo’s name.

Dr. TooToo Medvalli – Available

Sogamawa crouched down, bringing his face level with TooToo’s. This close, TooToo could see the details—the expensive moisturizer, the precisely trimmed eyebrows, the faint lines around the eyes that spoke of stress managed through spa treatments rather than resolved.

“You can go now,” Sogamawa said.

“You’re letting me go?”

“You’re compliant. There’s nothing left to document.”

Leonardo cut the zip ties. TooToo stood slowly, his knees aching, his wrists marked with red lines. The women in the chairs were still recording. The camera was still running.

“My phone,” TooToo said.

Sogamawa handed it to him. The Mobile Heartbeat app stared back, cheerful and green.

“You understand,” Sogamawa said, “that if you uninstall the app, we’ll know. The system monitors compliance. We’ll see your status go offline, and we’ll schedule another session.”

TooToo looked at the phone. Looked at Sogamawa. Looked at the camera.

“Can I say something for the documentation?”

“Of course.”

TooToo held up the phone, showing the green availability indicator to the camera.

“This app says I’m available. I’m not available. I’m standing in a windowless room after being bound and hooded by hospital administrators who forcibly installed software on my personal device. I am, in every meaningful sense, the opposite of available. But the app says I’m available, and the app is what matters, because the app is what gets documented, and documentation is what gets measured, and measurement is what gets managed, and management is what this institution believes healthcare to be.”

He pointed at Sogamawa.

“This man went to medical school. He took the same oath I took. He promised to do no harm. And today he supervised the physical restraint of a colleague over a software installation. That’s what the MBA does to medicine. That’s what optimization culture does to physicians. It turns doctors into enforcers and hospitals into compliance factories.”

He lowered the phone.

“I will not uninstall the app. I want it on my phone. I want the green dot. I want the lie to be visible, documented, recorded—evidence of what compliance actually means in this institution. When a patient has an adverse event because a nurse believed Mobile Heartbeat delivered a message that it didn’t, I want this video to exist. I want people to see what this hospital’s leadership values.”

He walked to the door.

“Dr. Medvalli,” Sogamawa said. “This is documented.”

“I know.” TooToo opened the door. “So is this: you used to be a doctor. Now you’re a loser in a nice suit.”

He left the door open behind him.

Epilogue: Six Months Later

Dr. TooToo Medvalli was not offered contract renewal at MFWN. The documentation cited “cultural misalignment with institutional values.” The video of his compliance session was never released, but it was never deleted either. It sat on a server somewhere, preserved for documentation purposes, evidence of a problem that had been solved.

TooToo kept the app on his phone. He kept the green dot. He showed it to colleagues at conferences, at job interviews, at late-night gatherings where physicians shared stories of administrative absurdity.

“They hooded me,” he would say, showing the pulsing green indicator. “They bound my wrists. They forced my face into the camera to unlock my phone. And then they installed an app that says I’m available. That’s what modern healthcare leadership looks like. That’s what happens when MBAs run medicine.”

People laughed. People shook their heads. People said “that’s insane” and “that couldn’t really happen” and “you should sue.”

TooToo never sued. Lawsuits required documentation, and documentation was their language, not his.

Instead, he heard about an opening in Alaska. A small town called Ketchikan. A hospital called PeaceHealth. They needed hospitalists, and they didn’t ask about his communication preferences during the interview.

He took the job.

He brought the pager.

He kept the app installed—a small green lie, pulsing in his pocket, a reminder of what he was leaving behind and what, perhaps, lay ahead.

* * *

Trisha Morgan downloaded Mobile Heartbeat voluntarily the following week. She did not attend a compliance session. She did not ask what had happened to TooToo. Some questions were better left undocumented.

Dr. Richard Shih left MFWN four months later. His exit interview cited “better opportunities.” The documentation noted his departure as voluntary.

The very old cardiologist died. His son inherited the smartphone. The Mobile Heartbeat app continued to show the cardiologist as “available” for three weeks after the funeral, until someone in IT finally updated the status. For twenty-one days, the dead man had a green dot.

Dr. Sogamawa was promoted to Regional Chief Medical Officer. His new office had floor-to-ceiling windows and a view of the river. He never wore a white coat again.

ATTACHMENT

Sampling of user reviews for the MH-Cure application (iOS: 2.2/5 stars from 20 ratings; Android: 1.3/5 stars from 12 ratings). Selected review: “Mobile Heartbeat is an unreliable communication app… This week mobile heartbeat was not working and we had no way to communicate with other departments in the hospital. This is 100% unacceptable.”

The review was documented.

The app was not changed.

The green dots kept pulsing.

DISCLAIMER: The Last Download is a work of satirical fiction. All characters, institutions, and events depicted are entirely fictional. “The Medical Factory Without a Name,” “Slow Rapids, Michigan,” Dr. TooToo Medvalli, Dr. Sogamawa, and all other persons and places are products of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual healthcare institutions is purely coincidental. The “compliance session” depicted is an absurdist exaggeration intended as satire—no actual hospital would hood and restrain physicians over app installations. Probably. The app reviews quoted in the attachment, however, are inspired by real user feedback. This story is intended as commentary on healthcare administration culture, communication technology mandates, and the growing tension between institutional metrics and clinical reality. It should not be construed as medical advice, legal advice, or instructions for resisting your own hospital’s IT department.